On this page:

✔️ Motivation

✔️ Background Info

✔️ An example

✔️ Your Task

✔️ Requirements

✔️ Handing in

✔️ Grade Breakdown

Motivation (Why are we doing this?)

This lab will help you solidify your understanding of recursion.

Background Info

Recursion is the practice of breaking a complicated problem down into small, trivially solvable pieces, and then merging those pieces together to solve the full problem completely. Today you will be implementing a few recursive algorithms. The neat thing about recursion is that you can solve problems with a relatively small amount of well thought out code.

Quick Review of Recursion

In its simplest form, recursion is simply when a function calls itself within its own body:

- When a recursive function calls itself, a new stack frame is pushed onto the call stack with a slightly different set of parameters (if the parameters do not change it may recurse forever!).

- Calling itself allows the function to start again from the first line using the new parameters.

- The function call associated with this new stack frame will likely reach a point where it calls itself again, creating yet another stack frame with, again, with slightly different parameters.

- This process repeats until the base case is reached.

At first, this may seem like an infinite loop of sorts, but if the function is implemented correctly, the input should be modified at each call such that the parameters get closer to triggering the base case:

- In the base case, some non-recursive code is executed, and the function is able to return to whichever stack frame came before it, picking up where it left off.

- One by one, each call to the recursive function will complete, having done some processing on the input, and return its own result.

- If the function is implemented without a base case, or continually recurses without reaching one, the program will instead crash with a stack overflow error.

How to think about recursive function calls

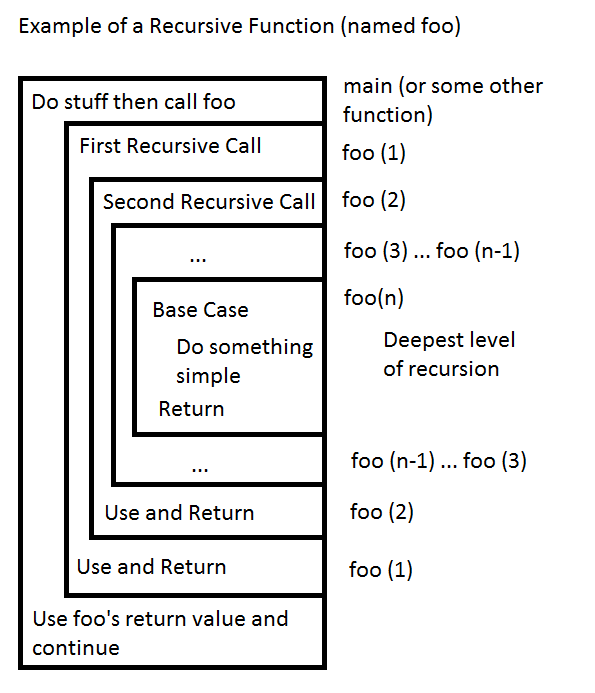

In the above diagram, each box is a call to the recursive function foo. In the base case, simple, often times even trivial, steps are taken for some special case of the input. After returning from the base case, each call to foo may use the result returned to it and return to its caller.

Note: Each deeper level of recursion is solving a smaller problem, so when you think of a recursive algorithm, you will often ask yourself three questions:

- “How can I make this input smaller?”

- “What is the base case I am working towards?”

- “How do I use solutions to the smaller problem to solve the bigger problem?”

Below you’ll find another visualization for recursion, this time for 5! (five factorial). As a reminder, n! is calculated by multiplying all of the numbers from 1 to n, so in this case: 5*4*3*2*1. Since we are repeating the same operation with a constant change in input, this is a function that recursion would come in handy for!

If we answer the three questions above for calculating factorials:

- “How can I make this input smaller?”

- The number I’m using decreases by one each time

- “What is the base case I am working towards?”

- The base case,

1!, equals 1

- The base case,

- “How do I use solutions to the smaller problem to solve the bigger problem?”

- Since

5! = 5*4*3*2*1this can be rewritten as5! = 5 * 4!and4! = 4 * 3!and so on and so forth.

- Since

An example: Sum of Numbers

Before you begin implementing recursive algorithms for yourself, you’ll be guided through each step of a recursive implementation of the sum from 1 to n. Along the way, you will see which part of the algorithm corresponds to which concept, and hopefully you will get a better understanding of how to think about a recursive algorithm.

First, download or copy the contents of sum.cpp. All you have is a small main and an empty function sum which presently returns 0. Enter each of the following lines after reading the description for each, starting at line 4.

if (n == 0) {

return 0;

}

For most recursive algorithms, the best place to start is the base case, and since it’s so important (and allows you to end your function early with a return) it will often be at the top. The base case should be a small sub-problem which can be solved easily. In this case, sum(0) should sum no numbers from 1 to n, so it is defined to be 0, which will be a useful value when we consider the recursive step. Thus, you should note there are two important things going on here: we are checking for the base case with n == 0, and we are solving the base case by returning 0.

unsigned long sub_sum = sum(n - 1);

To reach this line, the base case must be false (n != 0), and so we must now recurse. We have already solved the question asking “what is the base case?” so now we address “how can the input size be reduced?”. Observe that the sum of all numbers from 1 to n uses the sum of all numbers from 1 to n-1 in the result, so we can get that sum by calling sum(n - 1) and storing it in a variable. Now we should have the solution to a smaller problem, which we can use in the solution to the whole problem.

Note: Often times instead of storing the value of the recursive call in a variable we will use it directly, either in some other computation to be stored in a variable or right in the return statement itself.

unsigned long total = n + sub_sum;

Finally, we address the third question: “how can the solution to the smaller problem be used to solve the whole problem?”. In this case it is fairly trivial, in that since we’re summing the numbers from 1 to n, and we have the sum from 1 to n-1, we can just add n to the sum from 1 to n-1 to obtain our solution. However, in many algorithms this question is not so trivially answered, and sometimes this part, which is sometimes called the combination step, requires a whole separate algorithm to solve. This what is meant by the “use” part of “use and return” in the diagram at the beginning of the lab.

Note: In some recursive problems, such as Fibonacci, there will be more than one sub-problem needing to be solved, requiring multiple recursive calls, typically with different inputs. In such cases, the combination step requires combining the solutions to all the sub-problems to solve the whole problem. On the other hand, sometimes there is no combination step required, despite there being recursive calls. This is often the case with recursive functions with side-effects.

return total;

The final problem to address is that sum is still returning 0, so we will now have it return total. Keep in mind that if some function other than sum is being returned to, then total represents the final solution: the sum from 1 to the original input n. However, if it is returning to another call to sum, then total represents the sum from 1 to n-1 from the perspective of the call it is returning to.

At this point you can compile and run sum.cpp. Since sum is called on 10 and on 100, you should get 55 and 5050 respectively. For the case of 10, you can see that the algorithm will give you the following

sum(10) = 10 + sum(9) = 10 + 9 + sum(8) = … = 10 + 9 + … + 2 + 1 + sum(0) = 55.

You should now take a moment to consider what the time complexity (big O) of this function is. Despite not having analyzed recursive functions before, you should still be able to come up with an answer and a good reason for it based on what you have seen in class.

Your Task

Work on these problems for about an hour, then you’ll be placed in random groups to discuss approaches, obstacles, and answers.

- Determine the Big-O of

sum()from the previous section. - Write and test a recursive function to compute the factorial of a given integer n. Determine its Big-O.

- Write and test a recursive function that returns the largest value in an array of integers. Determine its Big-O.

- Write and test a recursive function to generate the Fibonacci Sequence to the nth term. Determine its Big-O.

-

Write and test a recursive Un-ordered Permutation function as described below: Given the value of N, output all permutations of numbers from 1 to N.

Input : 2 Output : 1 2 2 1 Input : 3 Output : 1 2 3 1 3 2 2 1 3 3 1 2 2 3 1 3 2 1Note: There are many ways to generate all unordered permutations of a given set. Your output does not need to match this example exactly.

Questions like task items #4 and #5 are commonly used as the first challenge problem the software engineering interview process, and they determine whether you can move on to the next step of the process. Understanding how to approach these problems is an acquired skill that we hope you’ll continue to acquire throughout the class!

Requirements

Work on these problems for about an hour, then you’ll be placed in random groups to discuss approaches, obstacles, and answers.

- Complete and be able to explain your solution to task 1.

- Complete and be able to explain your solution to task 2.

- Complete and be able to explain your solution to task 3.

- Complete and be able to explain your solution to task 4.

- Complete and be able to explain your solution to task 5.

Handing in

Recursion is required pre-requisite knowledge for the topics we’ll be covering the rest of the week (and semester!). You should work on these recursive problems for about an hour, then you’ll be placed in random groups to discuss approaches, obstacles, and answers. At the end of class we’ll have an “exit ticket” (mentimeter) asking how it went. Code solutions will not be collected but you should complete as much as you’re able to before being placed into random breakout groups.

Grade Breakdown

Recursion is required pre-requisite knowledge for the topics we’ll be covering the rest of the week (and semester!). You should work on these recursive problems for about an hour, then you’ll be placed in random groups to discuss approaches, obstacles, and answers. At the end of class we’ll have an “exit ticket” (mentimeter) asking how it went. Code solutions will not be collected but you should complete as much as you’re able to before being placed into random breakout groups.

Original assignment by Dr. Marco Alvarez, modified assignment version by Christian Esteves, used and modified (again) with permission.